After Closer to the Heart, I can understand that many readers might expect me to approach the newest book in Mercedes Lackey’s Herald Spy series, Closer to the Chest with trepidation. To be honest, I expected to approach it that way as well. The title gave me pause—if we are now closer to the chest, we are, technically, an inch or two further away than we were in the title of the last book. It turns out, though, that my childhood programming is impossible to overcome.

Earlier stories in this series brought us gun runners, thrilling late-night climbs up the sides of buildings, an unexpected glut of strawberry shortcake, and a tantalizing hint of the internal politics of Menmellith. I’m excited to find out what new kinds of dogs Lady Dia can breed (if we had Warming Spaniels, muffs would still be in), where else Mags will play Kirball, what his personal collection of orphans is going to do, and where the current trends are headed in Valdemaran cuisine. My personal vote is for truffle-hunting corgis, on a cultural exchange with the tribes who live north of Sorrows, forming a theater company, and funnel cake. Lackey doesn’t necessarily follow up on the issues I would like to see examined in more detail, but she knows how to keep her readers’ attention. Closer to the Chest is a lot of fun to read.

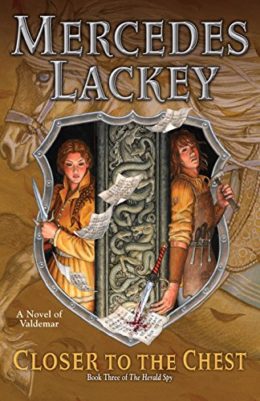

The cover art uses a lot of brown. In the center, a shield is divided into thirds. The leftmost third features a woman. I assume this is Amily incognito, or possibly with candlelight lending some color to her Whites. She is holding a knife, and looking very threatening. It’s a good look for her. Some documents float through the air, an interesting and perhaps unintentional reminder that Valdemar’s government recycles paper. In the center, a bloody knife impales another document in front of a stone column carved with a motif of Companions being attacked by snakes. On the right, a tired man with disheveled hair holds a hammer like it is his only friend in the world. It looks like Timmy fell down the well Mags got kidnapped again, and Amily is relying on Tuck to create a fabulous device that will help her find him and set him free. In the background, a riderless Companion gallops through something brown. It could be the Dhorisha Plains. It could be anything!

The cover is somewhat misleading. Tuck doesn’t make an appearance in this book, nor did I particularly notice any hammers. There are no snakes. And while I turned every page wondering whether Mags would still be a free man at the top of the next one, he was not abducted. Everyone stays in Haven. The cover is not entirely misleading: There is one thrilling headlong run on a Companion, and some bloodstained letters. Amily does, at long last, share the spotlight with Mags as protagonist. She’s not running across any rooftops, which is a sad waste of her talents, but she’s at the center of the story in her own right and no longer simply orbiting her partner.

Closer to the Chest is unusually sensitive to the struggles of the adolescent reader. Adult characters take the time to point out that everyone assumes that the personal drama of their own teenage years was the most extreme version available, and that kids today have very little to struggle with. Children from comfortable backgrounds tend to be the most judged—their lives are assumed to be free of struggle and any difficulties they encounter are thought to be minor. But, Lackey reminds us, everyone is on their own path, and just because some of the routes through the woods are more direct than others doesn’t mean that any of them are free from danger. While characters like Mags, with his deprived childhood as an enslaved mine worker, and Amily who was paralyzed until relatively recently, definitely had to work harder than others to overcome their difficulties, other young characters struggled too. And while later, more mature, evaluation may deem these trials trivial, they can seem pretty darn dramatic while they are in progress.

Having established that no one’s life is free from sorrow, Lackey moves into an unusually current issue for a pre-industrial society—Valdemar has developed internet trolls. Valdemar has not, of course, developed an internet. The height of Valdemar’s technological advancements will be achieved several hundred years after this book when some earnest young unaffiliated students build, and then blow up, a steam engine. The Collegia of Mags and Amily’s day don’t even appear to be using bulletin boards for community announcements. This limits our trolls to harassing their victims through letters and attacks on local businesses. This is more than adequate scope for damage to individuals and communities.

Valdemar’s particular troll infestation is carried out by men’s rights activists. It’s not surprising that Valdemar would be vulnerable to these. The cultural schism between Valdemar’s people and its ruling elites has been a theme of several books so far. Most ordinary Valdemarans, including its nobility, live in a society where monogamous heterosexual relationships and binary gender roles are expected norms and outsiders are regarded with fear and suspicion. Herald inhabit the same geographic space, but operate within a paradigm of gender equality and acceptance of all consensual adult relationships. They seek to develop greater understanding of new communities they encounter. The coexistence of these disparate cultures doesn’t appear to be changing either of them. This moment in Valdemar’s history makes the tension particularly acute; Amily’s father’s death allowed Rolan to choose her as King’s Own, but his revival leaves him lurking on the scene, still picking those parts of the role that he and King Kyril feel suit him best. Amily’s status is unambiguous to Heralds (and to Lackey’s readers, who are intimately familiar with how this system works)—Rolan chose Amily and she is the King’s Own. But it’s confusing to others, including many members of Kyril’s Court and the surrounding community. Amily is vulnerable to the assertion that she somehow stole her father’s role and should give it back. This was not the catalyst for Haven’s current problems, but it is an aggravating factor.

It would be easy for a writer working within a fantasy world to apply a simple solution to this complex problem. I’m grateful that Lackey has chosen not to. The current crisis is resolved as the story wraps up, but it’s clear that the underlying challenges remain. We’re starting to look at a much more critical view of Valdemar. Heralds are great, but they have a limited repertoire of solutions and they persistently refuse to examine some of Valdemar’s problems. Neither Lady Dia’s dogs, Mag’s very powerful Gifts, not Amily’s Animal Mindspeech make much of a difference here. It seems that MRAs do not own pets.

The difficulties that these characters find themselves in—the emotional crises, and the limitations on their abilities—make Closer to the Chest feel more like classic Valdemar that other recent volumes in the series. Valdemaran cuisine is undergoing a pie-centric renaissance. Lady Dia can breed tiny dogs that keep your hands warm, and huge ones with incredibly sensitive noses, but not medium-sized ones with a reliable alert bark. Mags’s orphans mostly just learn to read, and no one travels very far at all. I didn’t get exactly what I wanted out of this book, but it is an interesting and satisfying read.

Closer to the Chest is available now from DAW.

Join us for the ongoing Valdemar Reread.

Ellen Cheeseman-Meyer teaches history and reads a lot.